"The Gift of Failure"

Jessica Lahey's book "The Gift of Failure" serves as a reminder to parents and educators that failure is a gift which helps children learn.

With respect to grades, Lahey recounts an essay by a high school student who wrote:

"Before third grade, when scores and percentages did not matter, I wrote freely and honestly about what made me happy. But then foreign numbers began appearing on my papers, numbers representing other people's approval or disdain. At first those numbers were inconvenient little shapes that hindered my ability to write without care. But soon I began to rely on those numbers. I became addicted to A's, craving more when I got snatches of praise. And I started to drift away from what I had been writing as a younger child. Before I realized it, I was writing for those little, crawling black shapes and red marks" (226).

Last week my 13 year old daughter, India, started working on a presentation about teen cell phone use. The premise of her argument is that teens are addicted to their cell phones. As part of the presentation, India has to involve the audience but she was struggling to come up with an idea. She eventually decided that she wanted to collect her classmates' devices at the beginning of her presentation to illustrate how uncomfortable it is to be disconnected even for a few minutes, but she didn't feel that this was reason enough to collect the students' cell phones and figured that her point would be lost. Instead, she decided to create a quiz using kahoot.it, which will test what her classmates can remember from the presentation. This is something that her teachers have done and she feels pretty safe doing herself.

When I asked India if she thought the quiz would help make her point -- teens are addicted to their cell phones -- she said she wasn't sure but she knows that it will involve the audience, which is something that she's expected to do as part of her presentation. I suggested that maybe there was something more she could do that would not only involve the audience but would also support her argument. After we spent time thinking about other possibilities and with input from her 14 year old sister, we came back to the idea of collecting cell phones.

India came up with a scenario where she would collect students' cell phones in a garbage bag, which she would switch with another bag that contains plastic CD cases. After making the switch, she would dramatically pull out a hammer and smash the cell phones (i.e. CD cases) thereby causing the audience to react in a manner of shock, desperation and anger (i.e. like an addict whose drug, or in this case cell phone, is taken away and destroyed). What a brilliant idea, right? Wrong.

Although India felt that the switcharoo would help make her point, she was worried that her classmates and teacher may get angry because everyone would think that she destroyed their devices. The kahoot.it, on the other hand, is something that works and she knows that her classmates and teacher will like the activity. In her words, "It doesn't really matter, dad. As long as I do something that involves the class, I'll get a good mark." Just like Lahey's student, India is creating work "for those little, crawling black shapes and red marks."

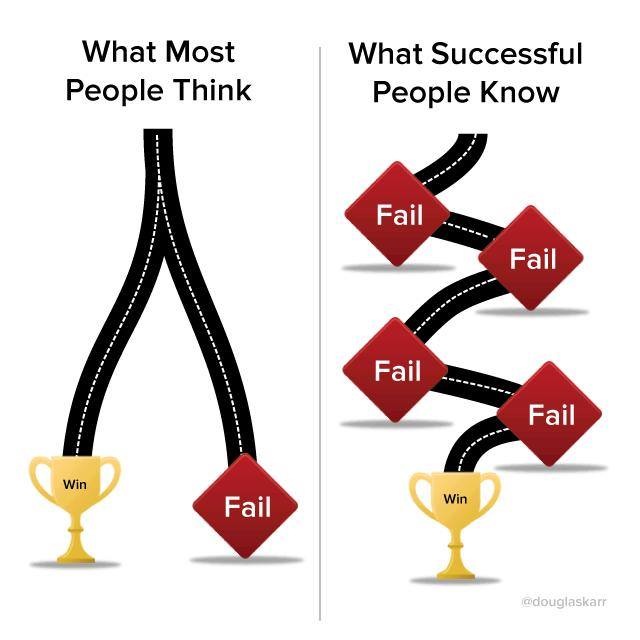

My wife and I encourage both of our girls to focus on learning and not on grades -- a difficult concept to explain for sure. Of course, some people, including India and Maia, argue that learning and grades are dependent on one another; however, as we know from Carol Dweck's work, a poor result on a test or assignment is an indication that a student is not there "yet." The grade should help communicate to the student, teacher and parents what the student has learned and what they still need to work on. It should be seen as an opportunity to learn and grow, as a means to an end; however, most students and many teachers and parents believe that the grade is the end, which is often the case. After an assignment or test is completed, especially at the end of a unit, students are rarely given a further opportunity to demonstrate their learning aside from the final exam, which might be several weeks or even months after the unit is completed. As a result, students like India who genuinely care about doing well in school, will avoid taking risks because they associate "doing well in school" with getting good grades. Failure in her mind is definitely not a gift.

If you're reading this, you're probably a like-minded teacher or parent -- you understand the gift of failure. I want to encourage you to continue your efforts to help others understand that failure is an important iteration of learning. In your conversations this week with students, parents and your children, challenge them to focus on learning and not on grades. I'll do the same.

With respect to grades, Lahey recounts an essay by a high school student who wrote:

"Before third grade, when scores and percentages did not matter, I wrote freely and honestly about what made me happy. But then foreign numbers began appearing on my papers, numbers representing other people's approval or disdain. At first those numbers were inconvenient little shapes that hindered my ability to write without care. But soon I began to rely on those numbers. I became addicted to A's, craving more when I got snatches of praise. And I started to drift away from what I had been writing as a younger child. Before I realized it, I was writing for those little, crawling black shapes and red marks" (226).

Last week my 13 year old daughter, India, started working on a presentation about teen cell phone use. The premise of her argument is that teens are addicted to their cell phones. As part of the presentation, India has to involve the audience but she was struggling to come up with an idea. She eventually decided that she wanted to collect her classmates' devices at the beginning of her presentation to illustrate how uncomfortable it is to be disconnected even for a few minutes, but she didn't feel that this was reason enough to collect the students' cell phones and figured that her point would be lost. Instead, she decided to create a quiz using kahoot.it, which will test what her classmates can remember from the presentation. This is something that her teachers have done and she feels pretty safe doing herself.

When I asked India if she thought the quiz would help make her point -- teens are addicted to their cell phones -- she said she wasn't sure but she knows that it will involve the audience, which is something that she's expected to do as part of her presentation. I suggested that maybe there was something more she could do that would not only involve the audience but would also support her argument. After we spent time thinking about other possibilities and with input from her 14 year old sister, we came back to the idea of collecting cell phones.

India came up with a scenario where she would collect students' cell phones in a garbage bag, which she would switch with another bag that contains plastic CD cases. After making the switch, she would dramatically pull out a hammer and smash the cell phones (i.e. CD cases) thereby causing the audience to react in a manner of shock, desperation and anger (i.e. like an addict whose drug, or in this case cell phone, is taken away and destroyed). What a brilliant idea, right? Wrong.

Although India felt that the switcharoo would help make her point, she was worried that her classmates and teacher may get angry because everyone would think that she destroyed their devices. The kahoot.it, on the other hand, is something that works and she knows that her classmates and teacher will like the activity. In her words, "It doesn't really matter, dad. As long as I do something that involves the class, I'll get a good mark." Just like Lahey's student, India is creating work "for those little, crawling black shapes and red marks."

My wife and I encourage both of our girls to focus on learning and not on grades -- a difficult concept to explain for sure. Of course, some people, including India and Maia, argue that learning and grades are dependent on one another; however, as we know from Carol Dweck's work, a poor result on a test or assignment is an indication that a student is not there "yet." The grade should help communicate to the student, teacher and parents what the student has learned and what they still need to work on. It should be seen as an opportunity to learn and grow, as a means to an end; however, most students and many teachers and parents believe that the grade is the end, which is often the case. After an assignment or test is completed, especially at the end of a unit, students are rarely given a further opportunity to demonstrate their learning aside from the final exam, which might be several weeks or even months after the unit is completed. As a result, students like India who genuinely care about doing well in school, will avoid taking risks because they associate "doing well in school" with getting good grades. Failure in her mind is definitely not a gift.

If you're reading this, you're probably a like-minded teacher or parent -- you understand the gift of failure. I want to encourage you to continue your efforts to help others understand that failure is an important iteration of learning. In your conversations this week with students, parents and your children, challenge them to focus on learning and not on grades. I'll do the same.

Comments

Post a Comment